Mount Lowe Railway

Mount Lowe Railway | |

Opening Day ceremonies of the Mount Lowe Railway at Mountain Junction, the corner of Lake Avenue and Calaveras Street, Altadena, July 4, 1893 | |

| Location | Mount Lowe |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°12′40″N 118°07′14″W / 34.21111°N 118.12056°W |

| Built | 4 July 1893 |

| Architect | David J. Macpherson |

| NRHP reference No. | 92001522 (original) 14001146 (increase) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 6, 1993 |

| Boundary increase | January 14, 2015 |

| Mount Lowe | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Defunct | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Pacific Electric | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Southern California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Light rail, Funicular | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Pacific Electric | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Pacific Electric | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1902 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 1938 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) (Mountain Division); 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge (other divisions) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | Overhead line, 600 V DC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

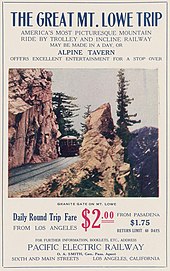

The Mount Lowe Railway was the third in a series of scenic mountain railroads in the United States created as a tourist attraction on Echo Mountain and Mount Lowe, north of Los Angeles, California. The railway, originally incorporated by Thaddeus S. C. Lowe as the Pasadena and Mt. Wilson Railroad Co.,[1] existed from 1893 until its official abandonment in 1938, and was the only scenic mountain, electric traction (overhead electric trolley) railroad ever built in the United States. Lowe's partner and engineer was David J. Macpherson, a civil engineer graduate of Cornell University. The Mount Lowe Railway was a fulfillment of 19th century Pasadenans' desire to have a scenic mountain railroad to the crest of the San Gabriel Mountains.

The Railway opened on July 4, 1893, and consisted of nearly seven miles (11 km) of track starting in Altadena, California, at a station called Mountain Junction. Atop Echo Mountain was a 70-room Victorian hotel, the Echo Mountain House. A short distance away stood the 40-room Echo Chalet, which was ready for opening day. Other buildings on Echo Mountain included an astronomical observatory, car barns, dormitories, repair facilities, a casino and dance hall, and a menagerie of local fauna.[2]

For the seven years during which Lowe owned and operated the railway, it was not financially successful, and was eventually sold. A series of natural disasters destroyed the facilities, the first of which was a kitchen fire that destroyed the Echo Mountain House in 1900. Further fires and floods eventually destroyed any remaining facilities, and the railway was officially abandoned in 1938 after a flood washed railway property off the mountain sides. The ruins of Mount Lowe Railway remain. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 6, 1993, a listing that was enlarged in January 2015.

Physical description

[edit]

The railway terminal, called Mountain Junction, was located at the corner of Lake Avenue and Calaveras Street in the unincorporated community of Altadena. The line was divided into three divisions: the Mountain Division, the Great Incline, and the Alpine Division. The mode of locomotion was electric traction railway, and a cable driven incline funicular. Electrical power for the railway consisted of several power generating stations equipped with either gas engines or Pelton wheels, depending on the availability of mountain water.[3]

Mountain Division

[edit]The Mountain Division, originally built as a 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge[4] line, began with a trolley that ascended Lake Avenue to a turnoff near Las Flores Street, along a private right-of-way through the Poppyfields district, and proceeded into Rubio Canyon to the foot of Echo Mountain. Since this part of the line ran through the upper end of the residential community, it had station stops at Newkirk (Las Flores), Poppyfields, Hygeia (recovery hospital), and Roca before entering the Rubio Canyon. A transition bridge was installed to cross the Rubio Wash named Las Flores Bridge.[5] At Rubio there was a large platform that spanned the canyon with an integrated 12-room hotel, the Rubio Pavilion. Other features at the pavilion were a series of stairways and bridges that ascended the canyon for viewing some eleven waterfalls, all of which were named.[6] The Mountain Division's tracks were converted to 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) in 1903.[7]

Great Incline

[edit]From this platform[8] passengers could transfer to a 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge, three-railed inclined plane railway,[9] the "Great Incline," and ascend Echo Mountain (elevation 3,250 feet [990 m]). The Incline powering mechanism was designed by San Francisco cable car inventor Andrew Smith Hallidie. It had grades as steep as 62% and as slight as 48%, and gained 1,900 feet (580 m) in elevation. The Great Incline was the first of its kind built with three rails and featuring a four-railed passing track at the halfway point.[10] A particular feature on the Incline was the Macpherson Trestle named by Lowe for his engineer, David J. Macpherson, as was custom, and noted for its design in crossing a granite chasm over 150 feet (46 m) deep.[11]

Echo Mountain

[edit]

Lowe wanted to make the mountains overlooking Altadena and Pasadena accessible to average citizens. After much planning, and many exploratory trips on horseback, he and his engineer, Thomas McPherson, located a series of routes that could be built upon with a series of rail cars to reach miles back into the forest and eventually all the way to the top of Mount Wilson. Financing the project himself, Lowe proceeded to build the railway which eventually reached the base of Mount Lowe (named after Lowe, previously known as Oak Mountain). At its peak, it was the top honeymoon destination in the United States. Beginning with the red car lines in California, Lowe extended the line up through the hills in Rubio Canyon where a small hotel was built at the base of new incline rail systems that would take a visitor up a mile along a ridge overlooking the Los Angeles Basin to the top of Echo Mountain.

The top of Echo Mountain had restaurants, stores, dormitories for employees, and a power generating station to power Echo Mountain facilities. There was also a trolley repair building and pit, observation decks at various spots, trails that could be hiked up and down the mountain and into the Alpine regions, tennis courts, stables and a zoo. The entire assembly of buildings were painted white and because of the view from far below, became known as "The White City in the sky". The "opera box" great incline cars were also white and could be seen from afar ferrying up and down the hill. On a ridge behind the Echo Mountain ridge was an observatory building with a working 16-inch (410 mm) telescope housed in a round domed building. The extant foundations and cement telescope stand remain. Lowe intended to build the rail system all the way to the top of Mount Wilson along with additional hotels and facilities on the top. Later, much of the path of the large 100-inch telescope and observatory built on Mount Wilson was used to transport the delicate 100-inch (2,500 mm) mirror to the top of Mount Wilson.

Alpine Division

[edit]The third division, the Alpine Division, opened in 1896 and consisted of 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) narrow gauge[4] track with 127 curves and 18 bridges and trestles.[12] On this line there were three cars available for shuttling between Echo and the end-of-line, though only one car ever operated at a time due to electrical limitations, and there was no two-way traffic. The division spanned the broad face of Las Flores Canyon, rounded a promontory called the "Cape of Good Hope," traveled deep into Millard Canyon, reappeared at the front face of the mountain, and eventually disappeared into Grand Canyon where it terminated at the foot of Mount Lowe. This location was called Crystal Springs (elev. 4,995 ft or 1,522 m) for a stream of water that poured from the hillside, and it was here that the last of the hotels, the 12-room Swiss-style chalet, "Ye Alpine Tavern," was built.

History

[edit]The Mount Lowe Railway was born from a desire of the Pasadena Pioneers to have a scenic mountain railroad to the crest of the San Gabriel Mountains. A trail had already been established to the peak of Mount Wilson, but that trip was arduous and often required more than a day to travel up and down. Several proposals were floated to establish some sort of mechanical transportation to the summits, but they all lacked funding.

David J. Macpherson (b. 1854, Ontario, Canada), a civil engineer from Cornell University and a newcomer to Pasadena (1885), proposed a steam driven cog wheel train to reach the crest via Mount Wilson. It wasn't until he was introduced to the millionaire Thaddeus S. C. Lowe (arrived in Pasadena 1890) that a fully funded plan could be put into action. The two men visited Colorado to view the mountain railway to Pike's Peak. Lowe was impressed with the trolley car systems in the city and thought that should be the way to go. This would make the Mount Lowe Railway the only electric traction rail line ever to be put into scenic mountain railway service.

Incorporation

[edit]The two men incorporated the Pasadena & Mount Wilson Railroad Co. in 1891 with intentions to build the railroad to Mount Wilson. Unable to obtain rights of way to Mt. Wilson, Macpherson suggested an alternate route, toward Oak Mountain, a high peak to the west of Mount Wilson. They hired electrical engineer, Almarian W. Decker, who had contrived all the mathematical possibilities of an electric line and the funicular which would be required to ascend the Echo Mountain Promontory.

Construction

[edit]Mountain Division

[edit]Blasting into the Rubio Canyon began in September 1892,[13] three months before the establishment of the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve (now Angeles National Forest). A terminal was built at the corner of Calaveras Street and Lake Avenue in Altadena adjacent to the L. A. Terminal Railway station, and a narrow gauge line was laid up the 8% grade to a point near Las Flores Street where it turned eastward traversing the Poppyfields district and headed into Rubio Canyon.

At the Rubio division terminus was built a broad platform to span the Canyon which included the Rubio Pavilion, a 12-room hotel, with dining facilities and other amenities. The pavilion also consisted of power generating facilities with the use of gas engines and Pelton waterwheels. Water was made available from reservoirs built in the canyon's streams, though water was not always plentiful year round. As part of the entertainment experience, Lowe had a series of stairways and bridges built over the streams and waterfalls that emanated from the canyon. The 11 waterfalls were individually named and today exist as local landmarks.

The Great Incline

[edit]

Work was begun on the Great Incline, which featured such steep grades that no mule could be flogged enough into negotiating it. Instead, materials were carried up on the back of laborers; grading became a particular problem. While funiculars were usually considered to require four rails, two for the ascending car, and two for the descending car, there was not enough room to widen the grade to accommodate four rails. Over night the inventive Thaddeus Lowe came up with a plan to only use four rails where the cars pass each other and three rails on the upper and lower ends of the run, whereby the cars shared the center rail.[14] The ingenious three-railed funicular not only fit, but it also reduced the amount of required materials. This three-railed design has been applied on other places as well (e.g. Angels Flight).[citation needed]

A great feat of engineering was realized with a trestle that was built to negotiate a 150-foot-deep (46 m) granite chasm across 250 feet (76 m) of track on a 62% grade. The trestle was named, as was customary in railroad constructions, for the chief engineer, David Macpherson, thus, the Macpherson Trestle.[15]

The Great Incline cable mechanism was engineered by Andrew Smith Hallidie of San Francisco cable car fame. It climbed 2,200 feet (670 m) with approximately 6,000 feet (1,800 m) of cable spliced into a complete loop which raised and lowered the cars of the Incline. At the Echo summit an incline powerhouse was erected to house the winding motor and gear works which powered the 9-foot-diameter (2.7 m) grip wheel. The wheel consisted of 72 clamping "finger" mechanisms which bit down on the cable creating a smooth, non-slip actuation of the winding cable.[16]

The cable was a 1+5⁄8-inch (41 mm) steel cable spliced in two spots, one below each of the incline passenger cars and looped in a continuous strand around the grip wheel at the top of the incline and a tension wheel at the bottom. The cable was replaced every two or three years.[17]

The incline grade changed three times from a steep 62% grade at the base to a gentler 48% grade at the top, but the cars were designed to comfortably adjust to the differences in grade. The incline was also equipped with a safety cable which ran through an emergency braking mechanism under each car and provided an emergency stopping of the cars within 15 feet (4.6 m) should a failure of the main cable occur.

Echo Mountain

[edit]

The Echo Mountain site was ready for opening day, July 4, 1893, with the 40-room "Echo Chalet."[18] By November 1894 the 80-room Victorian "Echo Mountain House" was completed as a luxury facility to rival the Hotel Del Coronado in San Diego.[19]

Lowe also installed a 16-inch (410 mm) telescope and observatory on Echo, as he was a patron of the astronomical arts. He even sought to have the Mount Lowe Railway considered the astronomical center of the San Gabriels. He was even able to enlist astronomer Dr. Lewis Swift, whose reputation preceded him. Given the lack of light pollution in the area, Swift was able to discover some 95 new nebulae from the Echo vantage point.[20] ("It could be noted that in an earlier 1892 plan, Charles William Eliot President of Harvard University sought to have a 40-inch (1,000 mm) telescope put on Mt. Wilson. Lowe offered the use of his new Mount Wilson Railroad to transport the lenses up. However, the project benefactor died without leaving a trust, and the whole plan failed, and of course Lowe's train didn't end up going to Mt. Wilson either").[21]

Prof. Lowe's success was greatly drawn from his nationally renowned process of generating large amounts of hydrogen gas (see water gas).[citation needed] He had built a gas plant in Pasadena and had piped the gas some eight miles (13 km) to the top of Echo where there was a storage container seen in several earlier photographs.[22] The technology, mainly used for heating and lighting, was soon replaced by electricity.

Echo Mountain also sported a menagerie (zoo) which housed several species of local fauna: lynxes, raccoons, snakes, squirrels,[23] and even a black bear.[24] Alongside the zoo was a dormitory and shop facility for maintenance of the trains.

Lowe purchased a three million candlepower searchlight from the Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893.[25] The light was installed on Echo in 1894. So powerful was the light, that a claim by Lowe's publicist, George Wharton James, stated that he could read a newspaper by the beam of the light coming through his hotel window on Catalina Island. Exaggeration or not, the beam from the light did have a 35-mile (56 km) projection. Residents announcing their birthdays could have the light shone on their homes in the evening. It was also known to stir up a corral of horses, invade lovers’ privacy, and interrupt an evening's revival meeting.[citation needed] By the 1930s the light was considered a public nuisance and was shut off permanently.

The Alpine Division

[edit]

A third division, the Alpine Division, was begun in 1894 and took a lengthy stretch of narrow gauge track across three canyons to the foot of Mount Lowe (formerly Oak Mountain).[26][27] The line ran from alongside the incline landing where passengers could transfer directly to the next trolley. There were three trains available on this line, but the limited electrical power only allowed one at a time to travel.[N 1] The line set out across the broad Las Flores Canyon which gave a tremendous panorama of the Los Angeles area below. At one point a tall trestle was required to bridge a broad and deep chasm with a bridge so named High Bridge.

At the ridge which separates Las Flores Canyon from Millard Canyon, the right of way was cut around a bluff named Cape of Good Hope. On the back side of the bluff was a section of straight track labeled "longest straight track 225 ft [68.6 m]."[29] From there the rails led deep into Millard Canyon before making a complete turnabout at Horseshoe Curve and heading back to the face of the mountain.[30] Once again overlooking the valley, the train made a broad sweep around Circular Bridge. The design of the bridge, more a trestle, was to allow the trolley to negotiate a 12-foot (3.7 m) switchback, over 500 feet (150 m) of track, at a 4% grade in a 340° turn. The wooden structure resembled a section of roller coaster offering an awesome sight over the side of the car looking almost 100 feet (30 m) straight down.[31]

From the switchback the train made a return trip into Millard Canyon. At the transition point of Millard and Grand Canyons, construction was met by a large granite crag that required eight months of dynamiting and mucking to allow just enough passage for the narrow gauge cars. The site was named Granite Gate at 4,072 feet (1,241 m) in elevation.[32] The last stretch of track reached deep into Grand Canyon on a gentle grade that ended up at the foot of Mt. Lowe. There in a location called Crystal Springs, Lowe built a 12-room, Swiss chalet styled hotel named "Ye Alpine Tavern." It was also flanked by cottages and tent cabins to augment its occupancy. The Tavern boasted several amenities, such as a wading pool, tennis courts, mule rides, gift shop, restaurant, and a silver fox farm.

This spot marked the end of the line, nearly 7 miles (11 km) from its starting point at Mountain Junction.

Visitors

[edit]

The Mount Lowe Railway opened officially on July 4, 1893.[N 2] Folks amassed themselves at the remote Mountain Junction. Up to this point there was only one means of public transportation from the valleys below to the hillside community of Altadena. It was the Los Angeles Terminal Railway which by this time was running from Terminal Island in San Pedro to Mountain Junction. The trains ran twice a day, and very irregularly at that, so the only sure means of getting to Altadena on time was by your own horse and buggy. This lack of transportation, coupled with Lowe's inability to establish any at all, would be in part the downfall of the railway.

Nevertheless, over its 45 years of existence, it is estimated that some 3 million people had ridden the railway, many coming from all parts of the country and the world. In its own inimitable way, it was a Disneyland of the day. Lowe had two favorite days of the year, Independence Day and Christmas, during which he would mark special events of his lifetime.[N 3] A publication which emanated from the Tavern daily was the Echo, a preprinted newspaper with a blank page that had the names and home states of the daily arrivals surprinted. The four-page tabloid had three pages of biographical information on the railroad and other announcements of daily events.

At the top of the incline was perched Charles Lawrence, the official photographer, on a special scaffold from which he would take pictures of the arriving visitors.[33] For 25 cents, visitors could purchase a souvenir photo of their arrival on the incline car, with everyone else aboard, of course. George Wharton James, Lowe's publicist, had his own publication which touted the railway in its conception, construction, and operation.

Megaphones, called "echophones", were installed on Mount Echo through which visitors could bellow into the back canyons and receive a number of echoes. The "sweet spot" where the most repeaters could be heard had at least nine reverberations of anything that was shouted loud enough. The study of the sweet spot has even been used as boy scout projects.[citation needed]

Along the way in Millard Canyon, a special station stop was made at Dawn Station above the Dawn Mines, an old gold mining operation.[34] The mines were deep in the canyon and visitors stopping off to see the digs spent an exorbitant amount of time getting back to the train. A false pit was dug just a hundred feet below the track to trick people into thinking they had visited the mine and were shortly ready to return to the train.

The mountain itself offered a grand display of nature and hiking trails, plus a mule ride, the "Mount Lowe Eight," that transported guests around a trail. This trail made a large figure eight traverse of Mt. Lowe and Mount Echo, starting and ending at the Alpine Tavert without ever traversing the same terrain twice.[35]

In 1922 Henry Ford visited the Mount Lowe Railway and returned with a Hollywood filming crew who made a silent film documentary of the trip with the camera mounted on the various cars, including the Great Incline. A reel containing 618 feet (188 m) of this historic film is available at the Library of Congress.[36]

Troubled times

[edit]In all, there were four hotels along the line, but the extent of the construction and the poor patronage had stretched Lowe to his limit. By 1898 the railroad fell into receivership under Jared Sidney Torrance, founder of Torrance, California. Both men applied to the government for rights of way to the top of Mt. Lowe. The government realized that the whole railroad was on Federal property (vis-à-vis the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve) and demanded that a proper lease be taken out on the properties. Having reviewed Lowe's standing with the railway, Congress awarded the receivership to Torrance in 1899, and Lowe was left with only the title to the observatory.[1] It was at this time that the railway was reorganized and incorporated as the Mount Lowe Railway. The railway was sold at auction to a Mr. Valentine Peyton of Danville, Illinois, who personally came to California to run the operation.

Disasters strike

[edit]

In 1900, the Echo Mountain House burned down.[37] It was grossly under-insured and was never rebuilt. Later, the astronomer Dr. Swift went blind and was forced to leave his post at the observatory. A second astronomer, Prof. Edgar Lucien Larkin (1847–1925), was hired to oversee the observatory.[37] Though he was not as prominent as Prof. Swift, he did stay with the Mount Lowe Observatory until his sudden death in 1925. Disenchanted, Peyton sold the railway to Henry E. Huntington, after which it became part of the Pacific Electric Railway (PE), of the famed Los Angeles Red Car system.[38]

Part of the PE improvements included a "casino" on Echo Mountain. The building appears in a few rare photos and was described as a dance hall, not a gambling facility. Most historians[who?] believe that the casino was built only a few months before the fire of 1905. The blaze began when a forceful wind blew the roof from the casino onto the power generating station across the track, setting a fire that razed everything on Echo except the observatory and the astronomer's cabin.[39] The only part of the Echo operation that was restored was the Incline Powerhouse in 1906. Other improvements were made to the railway, such as the replacement of rock pile footings under each trestle with reinforced concrete pilings.[N 4]

In 1909, an unseasonable electrical storm and flash flood destroyed the Rubio Pavilion and buried one of the caretakers’ children in the mud.[40] The injured parents spent years in the hospital recuperating from the devastation that left them trapped in the rubble of the Pavilion. Three of the children, who knew how to move the incline cars, escaped to the top of the incline.[N 5]

In 1928 a strong Santa Ana Wind blew down the observatory. Its curator at the time, Mt. Lowe photographer Charles Lawrence, escaped the collapse within an inch of his life.[41] Fortunately, he had the foresight to pack up the expensive lens pieces ahead of time. The instrument has since been reinstalled at Santa Clara University.

In 1925 a large block brick annex was added to "Ye Alpine Tavern" and the facility was renamed "Mount Lowe Tavern." In September 1936 the tavern burned to the ground from an electrical fire.[42][17] The PE was officially out of business, but left train operators on the line, so as not to abandon the railway. Though there was a slight consideration to rebuild, lack of water, poor area for relocation, and the financial burden of construction and insurance left the PE all but giving up on the Mount Lowe Railway.

In December, 1937, the Railroad Booster's Club, enthusiasts of the PE Railroad, requested a final paid excursion on the line for photos and memorabilia.[43] A few months later, in March, 1938 a three-day deluge of rain destroyed what was left of the railway and stranded the caretakers on Echo for 17 days. Following this disaster, the railway was officially abandoned.[44]

Dismantling

[edit]The Red Car line ran into Altadena until 1941. At the onset of World War II, the dismantling of the Mount Lowe Railway was contracted to a scrapper who stripped the railway of all salvageable materials.[45] In 1959 the Forestry service began dynamiting the remains of buildings as "hazardous nuisances." In 1962 the Incline Powerhouse was dynamited, but the gear mechanism was placed as a monument to the enterprise.[46]

Historical landmark

[edit]In 1992 a committee of the Pacific Railroad Society, successors to the Railroad Boosters, began a project of "revealment" which, under the supervision of Mike McIntyre, Angeles National Forest archaeologist, sought to uncover the ruins of Echo Mountain. On January 6, 1993, the Mount Lowe Railway was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the Forestry Service dedicated a block of land for the monument that would encompass all the artifacts from the railroad. On July 4, 1993, a centennial celebration was held on Mount Echo, and a separate celebration was held on Macpherson Parkway in the Poppyfields district. Today care of the artifacts and other restorative projects are being carried out by the Scenic Mount Lowe Railway Historical Committee under the leadership of Brian Marcroft and John Harrigan. The committee has become a group of uniformed forestry volunteers who continue to work closely with the forestry headquarters in Arcadia, California.[47]

-

Three 1,600 pound motorized drive wheels and motor armature with a snow plow mounted on rails over the service pit. Recovered in 1993 from the downhill side of Echo Mountain.

-

A Spare flanged wheel and axle assembly kept at the Echo Mountain maintenance barn for repair of the cars moving from Echo to the Mount Lowe Tavern.

-

Cable drive bull wheel salvaged from the Incline Powerhouse prior to demolition in 1962. The assembly stands as a monument to the Mount Lowe Railway.

-

Cable drive with companion intermediate gear assembly and two 6-foot guide wheels which stood at the top of the Great Incline. The intermediate gear was one of two retrieved from the hillside via helicopter in 1993.

In 2005 Stacey Camp began an archaeological dig on a section of Mount Echo where there once stood a barrack for workers. The dig is part of Camp's Doctoral thesis and has come about by a grant from Stanford University and is also being coordinated with the Forestry Service.[48]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ [28] Photo shows all three cars in one shot, but actually this had to be staged since all three cars couldn't all run at the same time. The Alpine line was equipped with turnouts, but there was no advantage to running multiple cars.

- ^ Lowe had two favorite days of the year, Independence Day and Christmas, during which he would mark special events of his lifetime.

- ^ These figures have been roughly reckoned by reading the daily reports of the arrivals which were published daily in the Echo, MLR's official daily newspaper.

- ^ On page 71 of Seims' book is a photo of the dormitories which is described as the casino. Later Mr. Seims had explained the misidentity by revealing that it was the aged Dorothy Drew Schaeffer, of the Pavilion keeper's family, who had identified this photo as such. Obviously, her memory over time had failed her, coupled with the fact that the real casino was not around long before the fire had consumed it. The casino, so labeled by a sign over the door, was discovered in old photos in 1992 by the Scenic Mount Lowe Railway Historical Committee. Seims referred to this building as his "mystery" building he had seen in other photos of Mt. Echo but had not identified or shown in his book. Pasadena Star News accounts of the fire indicated that the roof was blown off the casino and onto the power generating station across the track which set the blaze

- ^ One of these children is Mrs. Dorothy Drew Schaeffer mentioned in the former note. The Incline cars were equipped with a bell ringing system, called the magic wand, by which a wired stick could be touched to an electrical stringer alongside the Incline, and a signal bell would tell attendants at either end that the cars were ready to be moved. The children used the wand.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Seims (1976), p. 33.

- ^ Seims (1976), chpt. 5.

- ^ Harrigan, John (2000). Mt. Lowe Power. John P. Harrigan. ISBN 0-9701445-0-4.

- ^ a b "Mount Lowe Line". Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 38, 62.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 57.

- ^ "Mount Lowe Timeline". Mount Lowe Preservation Society. 5 April 2012.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 54–55.

- ^ "Mount Lowe Line". The Electric Railway Historical Association of Southern California.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 42–46.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 116.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 156.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 37.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 34.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 42.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Veysey, Laurence R. (June 1958). A History Of The Rail Passenger Service Operated By The Pacific Electric Railway Company Since 1911 And By Its Successors Since 1953 (PDF). LACMTA (Report). Los Angeles, California: Interurbans. pp. 39, 40. ASIN B0007F8D84. OCLC 6565577.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 79.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 70.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 68, 94.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 76.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 87.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 80.

- ^ "Man, Mountain and Monument". Archived from the original on 2006-11-27.

- ^ Seims (1976), chpt. 3.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 165.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 161.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 164.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 166.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Seims (1976), pp. 149, 205.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 149.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 99.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 205.

- ^ a b Seims (1976), p. 121.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 123.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 131.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 145.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 204.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 206.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 209.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 212. The flood rained 8 inches (200 mm) of water in 100 hours.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 217.

- ^ Seims (1976), p. 218.

- ^ Dollins, Bob (2005). "Echo Mountain Resort Ruins".[self-published source?]

- ^ Stanford University and Angeles National Forest. "Mount Lowe Archaeological Project".

References

[edit]- Forbes, Armitage S. C. (November 1902). "The Ride Of The Iron Horse". XL (5): 417–427. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Larkin, Edgar L. (September 1902). "Stellar Research At Mount Lowe Observatory". Overland Monthly, and Out West Magazine. XL (3): 271–282. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- Rippens, Paul (1998). Historic Mount Lowe. self-published. ISBN 0-9663654-0-2.

- Seims, Charles (1976). Mount Lowe, The Railway in the Clouds. San Marino, CA: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-075-4. Lib of Cong CC# 76-45760.

Online publications

[edit]External links

[edit]- Professor T.S.C. Lowe website by Great Great Grandson

- Scenic Mount Lowe Railway Historical Committee

- Hiking Mt. Lowe Trails

- Mount Lowe Preservation Society

- Mount Lowe Archaeological Project

- The Mount Lowe Museum

- To Mount Lowe with Love (documentary)

- Mount Lowe Railway Route Map (from Google)

- Black, Brandon Lomenzo (January 8, 2019). "How An Arcadia Brewery Is Paying Tribute To SoCal's Fantastic, Forgotten Railway To The Clouds". LAist. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- San Gabriel Mountains

- Buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Los Angeles County, California

- History of Los Angeles County, California

- Altadena, California

- History of Pasadena, California

- Defunct California railroads

- Defunct funicular railways in the United States

- Electric railways in California

- Standard gauge railways in the United States

- Narrow gauge railroads in California

- Railway inclines in the United States

- 3 ft 6 in gauge railways in the United States

- Cableways on the National Register of Historic Places

- Rail infrastructure on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- 1893 establishments in California

- Railway lines opened in 1893

- Railway lines closed in 1941